Why Sri Lanka needs to address its policy on Vaping

By – Jithendra Antonio

The recent conversation at Sri Lanka’s Committee on Public Finance (‘COPF’) meeting on 11 March is a topic hotter than the coils in the ‘vapes’ that so many remain misinformed about. The reported snippets of the meeting, however, highlight the confusion among some policymakers regarding the legality and regulation of these vapour products (‘vapes’).

During the session, COPF members quite rightly questioned the current legal status of vapes and the missed opportunity for the government to collect more tax revenue. Despite their growing popularity, the legal status of vapes in Sri Lanka is ‘complicated’ to say the least, leaving a potential source of government revenue untapped.

So, what actually happens if you’re found with a vape?

The presumption of freedom

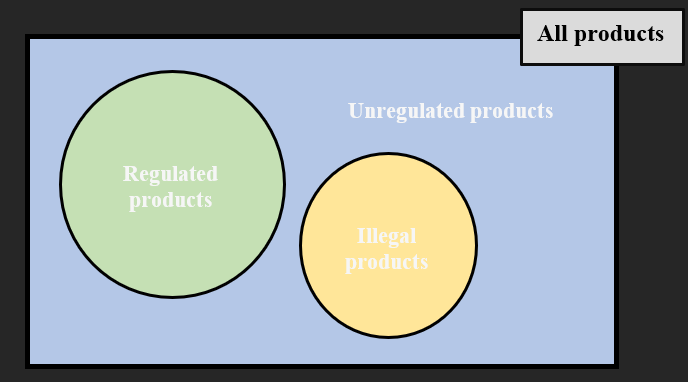

Products can be categorized based on their lawfulness and the degree of governmental oversight they require. The universal set in this Venn diagram represents ‘all products’. Some of these products fall into two mutually exclusive categories, namely ‘regulated products’ depicted by the green set and ‘illegal products’ depicted by the yellow set. Products that don’t fall into either category are in a state of limbo and are represented by the blue space, labelled ‘unregulated products’ for the purposes of this discussion.

The approach to unregulated goods can stem from one of two opposing schools of thought; one believes that individual liberty is paramount and operates on the principle that everything is permitted unless explicitly prohibited, while the other believes that nothing is permitted unless explicitly permitted by law.

This distinction begs the question: what do we do when something is neither regulated nor illegal? At present, vapes are one of these regulatory-outliers.

International practice

The legal classification of vapes vary significantly across jurisdictions, reflecting a spectrum of regulatory approaches influenced by differing philosophical and public health perspectives.

Sweden has arguably the most comprehensive regulatory framework and could serve as a good blueprint for other countries looking to do the same. While vapour products are legal in Sweden, they are subject to strict requirements. The product is required to be child and tamper proof with a maximum nicotine concentration of 20 mg/ml. Refill containers cannot exceed 10 ml, and cartridges are limited to 2ml. As for labeling requirements, the front and back surfaces of the packaging must contain text health warnings and should be accompanied by a content declaration and an information leaflet in Swedish.

The Sri Lankan context

The lack of clarity in Sri Lanka is not rooted in ambiguity in the law, but rather in poor understanding of vapour products. This confusion has led to a practice of ad-hoc crackdowns on these products resulting in arbitrary (and unreported) arrests and varying fines in some situations, and looking the other way in other situations.

Apart from the legal uncertainty and inconsistency in enforcement, this regulatory vacuum also presents serious health risks to consumers from unregulated products and leads to missed economic opportunities in generating government revenue through taxation. Sociologically and historically, the act of prohibiting has rarely yielded the intended result. The flagbearer of the concept itself – ‘the great prohibition’ in the 1920’s, although was well-intentioned, gave rise to what many consider to be one of the densest periods of organized crime as well as the mass production of poor quality and harmful counterfeits (‘moonshine’) of the very product it aimed to abolish. The correlation between prohibition and the rise of black-market alternatives is well-documented. When legal avenues for obtaining products are restricted, consumer demand often persists, leading to proliferation of unregulated and potentially more harmful alternatives. Brazil, for example has enforced a complete ban on vapes. Despite the ban, the black market for vapes is reported to be flourishing. A study by the University of Sao Paulo Institute of International Relations estimated that Brazil could forfeit approximately 7.7 billion reais (USD 1.4 billion) in tax revenue by 2025 from the illegal vape market.

A pragmatic solution to this problem would be to recognize smokeless nicotine products, such as vapes as a category distinct from cigarettes and regulate these products according to their risk profile. A clearer, sensible regulatory framework that covers vapour products and oral products that only contain nicotine as the primary component is therefore, required to advance legal certainty and ensure consumer protection.

Recent Comments